The Telos Method

According to Telos, sustainable development can be defined as a balanced increase in quantity and quality of three forms of capital:

•Ecological capital: nature

•社会文化capital: the physical and mental well-being of people

•Economic capital: healthy economic improvement

According to Telos, three criteria must be met before one can speak of sustainable development:

•The approach should be integral. Improvement of one capital cannot take place at the expense of one or both of the other two.1

•The development should be sustainable over time and throughout generations. Our children's and grandchildren's possibilities for development should not be eroded as a consequence of our own development.

•The development must be sustainable at the global level. Development here cannot take place at the expense of development elsewhere.

Sustainable development has a strategic (the long-term) and a normative (responsibility for other scale levels and future generations) dimension.

Guiding Principles

这将是有用的整体指导普林西普les for each type of capital in order to decide what the components should be and how they should guarantee balanced development. Telos has adopted the three principles defined by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (SFSO 2001): social solidarity, economic efficiency, and ecological responsibility. However, there is one difference: Telos prefers the term ecological resilience rather than ecological responsibility. This idea is taken from the International Center for Integrated Assessment and Sustainable Development (ICIS) (Rotmans et al. 2001).

Social Solidarity

Social solidarity consists of social equity and the quality of life. According to the SFSO (2001), each member of society is entitled to a dignified life and the free development of his or her personality, on the condition that the human dignity of other individuals and the living conditions of future generations are not compromised. Democracy, legal stability, and cultural diversity must be guaranteed. This implies a fair division of costs and benefits. Fairness is a difficult notion. The criteria to define it should be as neutral and consensual as possible. Telos has identified the following prerequisites: the existence of equal opportunities, the fulfillment of basic needs, and legal equality (Telos 2003).

Quality of life consists of the personal, physical, and social conditions that determine mental and physical well-being, including conditions with respect to housing, education, and health care.

Economic Efficiency

The second principle, economic efficiency, is about the ways individual or social needs are met. According to Telos (2002b), "the level of income should be sufficient enough to provide necessary needs. The available production means should be used as efficiently as possible, and without compromising future use." This definition fits with SFSO's (2001) description: "Economic activity must effectively and efficiently meet the needs of the individual and society. The economic framework must enable and stimulate personal initiatives, self interest must be put to service of the common interest and the welfare of the present and future generations must be ensured."

Ecological Resilience

According to the SFSO, ecological responsibility implies "preservation of the natural base of human life, repair of existing damage, and protection of the dynamic diversity of nature" (SFSO 2001). In other words, it is about reaching a balance between human use and ecological regenerative capacity. ICIS formulates it as follows: "In sustainableecological development, the development of the natural ecosystem comes first and preserving our natural resources plays a prominent part." Telos assumes a similar approach. The main concern is the preservation of the regulatory and habitat functions of natural ecosystems (Rotmans et al. 2001).

Monitoring Sustainable Development

To determine whether society is developing in a sustainable way, monitoring is needed. However, sustainable development is a multifaceted and multilevel notion. It is not only about the development of the three kinds of capital (ecological, sociocultural, and economic) but also refers to dimensions of time (now and later) and space (here and there). It is no coincidence that the first rule of the Bellagio guidelines for the assessment of sustainable development states, "Assessment of progress towards sustainable development should be guided by a clear vision of sustainable development and goals that define that vision" (Hardi and Zdan 1997).

In the case of the environment, the objectives for Brabant are clear and hardly controversial.2 The same is true for economic issues. Here the main problems are the assessment of future needs and wants and the questions whether and how nonhuman needs can be priced. The main obstacles in Brabant are in social capital (e.g., the problem of cultural diversity versus cultural homogeneity).

Telos has chosen a multilayered method to monitor sustainable development in the Dutch province of Brabant. This approach is related to the Bossel (1999) and ICIS methods:

•集成:经济、社会和生态interests and considerations are all taken into account at the same time.

•Interdisciplinary: Expertise from different scientific disciplines is integrated into one approach.

•Interactive: All stakeholders are involved, not just policymakers and scientific experts but social actors and professionals as well.

•Strategic: The focus is not on short-term problems but on long-term sustainability requirements (i.e., goals for sustainable development).

•Normative: Unwanted long-term effects are made explicit, with the help of experts and stakeholders.

•Indicative: Undesirable consequences or outcomes are made explicit. Relevant Terms

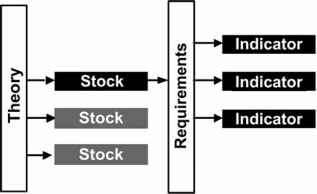

In the Telos method, a distinction is made between capitals, stocks, requirements, indicators, standards, and context variables. Box 19.1 gives brief definitions of these terms.

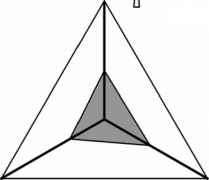

Capitals. Telos distinguishes three forms of capital: ecological capital, sociocultural capital, and economic capital. The range and development of the capitals are visualized by means of a sustainability triangle (Figure 19.1). We can discern two triangles: the main triangle and a smaller triangle.

The inside triangles indicate the actual condition of each capital. The larger ones represent the ideal situation for each capital. The ideal situation is based on science and the judgments of experts and stakeholders.

Stocks. In order to assess the condition of each capital, we have to find the components or essential elements that determine each capital. To develop an integrated perspective

Box 19.1. Definitions of relevant terms. |

|

Term |

Definition |

Capital |

The three essential aggregated subsystems of |

the total societal system: ecological, socio- |

|

cultural, and economic. |

|

Stocks |

The essential elements that together de- |

termine the quality and quantity of the capital. |

|

Requirements |

The requirements formulated with respect to |

the development of a stock. |

|

Indicators |

The degree to which the requirements are met |

is measured by means of indicators. |

|

Standards |

Normative criteria, developed by the stake |

holders, to assess the score of indicators. |

|

Context variables |

Variables that influence sustainability but can |

not or will not be influenced. |

|

C|j) Ecological capital ffl

社会文化capital

Economic capital

Figure 19.1. Telos sustainability triangle.

on sustainability, it is necessary to use identical notions and have a uniformanalytical framework. This was achieved by introducing the concept of stocks, which is used in system dynamics. Each capital consists of a number of stocks. Together they determine the quality and quantity of the capital as a whole.

The stocks were determined with the help of desk research and in workshops with experts and stakeholders (Box 19.2).

要求。下一步是使股票operational by introducing the notion of requirements, which are the main long-term goals. For each stock a small set of requirements was formulated. The content of a requirement was determined by asking the following question: "What should the contribution of each stock be to advance sustainable development (social solidarity, economic efficiency, and ecological resilience, here and elsewhere, now and in the future)?" This was done through expert judgment and stakeholder preferences. The first step was to consult experts; the next step was to reconcile their opinions with those of stakeholders. That was done in the form of workshops. This approach gives the method a strong normative undertone. According to Telos, this is consistent with the basic idea of sustainable development (WCED 1987; Dobson 1996, 1999; Holland 1999, 2000; Benton 1999).

For example, here are the requirements used for the labor stock in the province of Brabant:

Box 19.2. Stocks. |

||

社会文化 |

Ecological |

Economic |

Health and care facilities |

Nature |

Labor |

Solidarity |

Soil |

Capital goods |

Safety |

Deep groundwater |

Knowledge |

Cultural diversity |

Air |

Infrastructure |

Citizenship |

Surface water |

Economic structure |

Living environment |

Natural resources |

|

Education and |

||

training |

•The demand and supply of labor must be in balance, in number as well as in quality.

•Labor conditions must be good with respect to safety, health, working hours, and training facilities.

Requirements (but also stocks), by definition, can and will change. The nature of the requirements depends on the place, context, stakeholders, and experts involved and the time and scale.

Indicators. The degree to which the requirements or long-term goals are met is measured by means of indicators. For each requirement, one or more indicators must be found, such as the indicators used for the requirements with respect to the labor stock in the province of Brabant:

•Ratio between employment and resident labor force

•Use of the potential labor stock

•Labor market tension

•Educational match

•Initiation and aging

•Number of jobs in information and communication technology (ICT) compared with the total number of jobs

•数量的受过高等教育的人

To prevent an excess of indicators, a maximum of eight are established for each stock. Figure 19.2 represents the relationship between the different elements of the method. To sum up:

•Each capital consists of stocks.

•For each stock requirements are defined.

•Indicators show the degree to which these requirements are met.

图19.2。关系资本、股票、requirements, and indicators. Determining the Value of Stocks and Capital

To ensure that forms of capital and stocks can be compared, they should be indexed, weighted, and standardized.

Indexing. Indexing involves more than calculating and trying to determine the precise value of a capital or stock by means of counting and discounting. The value of all types of capital is equally important, and their sum is the sum of everything we value or should value. Furthermore, not all stocks contribute equally in all circumstances (qualitatively and quantitatively) to the value of a capital, and not all indicators are equally important in determining what the condition of a stock is. Therefore, a weighting procedure that pays attention to quantitative and qualitative aspects was built in. The first step in developing this instrument was to set the desired score for each indictor.

The Score of an Indicator. The first step is to specify the nature of an indicator and to decide what type of data is needed. Those data can be quantitative or qualitative. The qualitative indicators are also given a numeric score. The next step is to bring the measurement in line with the agreed-upon targets or end values. This is a specific normative procedure. However, it is important to work with target values and limit values that are as objective as possible. Therefore, we followed this procedure:

1. We looked for relevant scientific documentation.

2. If that was not available or did not provide adequate answers, we looked for standards laid down in government documents or governance-oriented studies.

3. If that did not help either, we looked to see whether there was social consensus among (possible) stakeholders on target values.

图19.2。关系资本、股票、requirements, and indicators. Determining the Value of Stocks and Capital

4. If that still did not deliver clearly delimited target values, we tried to define them ourselves by carefully comparing the findings with the topics they were supposed to measure and the requirements they were supposed to fulfill (see also Telos 2002a).

From this research, a scale of 1—100 can be designed, going from unacceptable to optimal. This scale is divided in four categories, symbolized by different colors. Each category also indicates the kind of action needed:

Red: Socially unacceptable (immediate action needed) Orange: Social limit (immediate attention needed) Green: Socially acceptable (short-term purpose) Gold: Socially optimum (long-term purpose)

For example, the ratio between employment and resident labor force is one of the indicators for the labor stock. This ratio indicates whether a region imports or exports labor. When stock and demand for labor are equal, the labor market is in balance. This optimum corresponds to a value 100. Some deficiency or surplus is acceptable, but as soon as the deficiency or surplus exceeds a certain degree, the labor market is in disorder.

Social optimum is 100.

Socially acceptable is 100 < x < 105 or 95 < x < 100.

Social limit is 105 < x < 110 and/or 90 x < 95.

Socially unacceptable is x > 110 or x < 90.

Weighting and Determination of the Extent of the Stock. Each stock receives a score on a scale from 1 to 100 for sustainable development. This is the weighted average of the indicators. The indicators have to be weighted because not every indicator is equally important when it comes to describing the stock.

For the labor stock, the indicators are weighted as shown in Box 19.3, and the outcome is illustrated in Figure 19.3.

The score of an indicator is shown by the degree to which a pie wedge is filled. The shades (or colors) represent the categories of the scores. The angle represents the weight of the indicator. The arrow represents the trend of development, if that can be determined. In this way the actual situation can be assessed immediately and compared with the desirable one for each indicator.

If the pie wedge is completely filled to the outer ring, the optimum situation is reached. This way, areas that need attention can be identified. In other words, Figure 19.3 indicates the current situation of the stock and shows where action is needed. The total score of a stock (the weighted average of the indicator scores) is represented as a bar chart.

Box 19.3. Labor stock. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Indicator |

Weight |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ratio of employment to labor force |

17% |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Use of potential labor stock |

20% |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Labor market tension |

9% |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Educational match |

17% |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Initiation and aging |

13% |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Number of information and communication technology jobs |

8% |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Number of highly educated people |

Ecological capital  Figure 19.3. Visual representation of the actual situation and the direction of development, by indicator. 社会文化capital Economic capital Figure 19.3. Visual representation of the actual situation and the direction of development, by indicator. Weighting and Determining the Value of the Capitals. The score of one capital is the weighted average of the stock scores. Not all stocks are equally important, so the stocks were weighted, like the indicators. The process of determining the sustainability triangle is summarized in Figure 19.4. By mapping out the scores per stock within a capital and by comparing them in time, we can ascertain whether there is progress in the desired direction. In each capital, progress is represented by the shaded part of the line expanding outward toward the corner of the triangle. Progress in capital as a whole can coincide with negative changes in one of its stocks if this is compensated by progress in one of the other stocks of the same capital.

Application of the Telos Method The Telos method was applied in four Dutch provinces: first in the province of Brabant, in 2000 and 2001, and then in 2003 in the provinces of Zeeland, Limburg, and Flevoland. When we started, we expected to find some dissimilarities between the provinces but not too many. However, the reality was different, and we found major differences. We discuss and analyze them in this section, first by looking at the process. For additional information, please see our Web site (www.telos.nl). The ProcessThe Telos method had already been applied in Brabant before it was used in the other three provinces. The idea was to use the method developed for Brabant as much as possible in the other regions. The stocks, requirements, and indicators defined in Brabant were used as inputs, and the intention was to use the same procedure for the other regions (i.e., to adapt, reject, or adjust them according to expert judgment and stakeholder views). In practice, the modus operandi in the other provinces was different. It was shaped far more by the provincial government and stakeholders' points of view than in Brabant (Figure 19.5). Region of Brabant Assignment (political) Analyze policy papers 利益相关者评估库存、需求和indicators by stakeholders Data collection New data in 2002 Publication and debate Three other regions Assignment (administrative) Administrative assessment of the model of Brabant

Figure 19.5. Differences and similarities between Brabant and the three other regions. In Brabant, from the outset there was political support for the idea of assessing regional sustainable development. In the other provinces, the political will was less pronounced. In all three provinces, the main supporters of the process were provincial civil servants. One explanation for this difference was the fact that this project was partly initiated and largely funded by the Dutch Ministry for Housing, Regional Development, and the Environment (VROM). The ministry wanted a general model for assessing sustainable development at the provincial level in the Netherlands (with a 75 percent overlap concerning requirements and indicators). Stocks, Requirements, and Indicators 如前所述,目的的第一步model is to determine the stocks, requirements, and indicators for each of the three forms of capital. In Brabant this was done in three steps. The first step was desk research, a thorough analysis of existing scientific publications and policy documents. The second step was to discuss the results of this research with experts and adapt them if necessary. The third step was to discuss these outcomes with a selected group of thirty stakeholders, consisting of key informants from all relevant sectors (government, civil society, business) in Brabant. They had to decide what the final stocks, requirements, and indicators should be. The decision was based on consensus. In the other three provinces, the procedure was somewhat different. The stocks, requirements, and indicators already defined in Brabant served as a starting point. They were presented in each of the provinces to a selected group of stakeholders, mostly provincial civil servants, as well as specialists and generalists. The procedure for doing this was as follows. After an introduction, where the method was presented along with the stocks, requirements, and indicators already defined in Brabant, subgroups were formed for each type of capital. Those subgroups were made up of officials from the province who were specialized in the policy fields relevant to the capital concerned. Each subgroup was given the assignment to examine the stocks, requirements, and indicators defined for Brabant and, if necessary, adjust them to local circumstances. Once this was done, we verified whether the outcomes formulated by those provincial civil servants were also accepted by the other categories of stakeholders. This was done in interactive sessions with selected representatives. When necessary, adjustments were made. The results of those sessions were presented and discussed again in a workgroup made up of some of the members mentioned earlier. This group made the final decision about what the stocks, requirements, and indicators should be. Operationalization and DataThe next step is the most labor-intensive one. The indicators are put into use and data are collected, processed, and weighted on the basis of these indicators. The first real obstacles appeared at this time. In Brabant and in the other three provinces, little time was available for this part of the process. We soon found out that much of the data needed were available only at the national level. Sometimes it was difficult to break these national data down into subsets usable at the regional level. Sometimes regional data available in theory were in fact not accessible. Even worse, sometimes the available data did not match the indicators, for quantitative or qualitative reasons. In fact, the process of collecting, interpreting, weighting, and combining regional data proved to be the main obstacle in the whole method and was very time consuming. Evaluation of the ProcessIn all four provinces, the learning process was considered as important as, if not more important than, the factual results of the assessments. The main purpose was to develop and test a method for assessing regional sustainable development. In 1999, when we started developing our method, well-developed models to assess regional sustainable development did not exist, although there already was a growing body of useful literature in principle. For instance, we used the studies of Hardi and Zdan (1997) and Bossel (1999). One of the few existing region-oriented methods was developed in British Columbia, but that approach differed from the method we had in mind. It opted for a strongly structured, statically based model (Pierce and Dale 1999; Robinson 1996). Our desire to emphasize the learning process was a good reason to call evaluation meetings with experts and stakeholders in all the provinces. A lot of useful comments came out of these sessions. The most relevant are as follow: Positive.•The reason why the elements that make up a capital are chosen and brought together is worked out well in the model. It also increases our insight into the ways they are connected. •The method reinforces and conceptualizes the interaction and communication between scientific disciplines, science and nonscience, and different arenas in society (policy, civil society, and business). •The method lends itself well to propagating the idea of sustainable development and the assessment of it on a regional scale to a wide audience. This is partly because of the simple and attractive way in which the concept and the results can be presented and visualized. Negative. •The connection and interaction between the three forms of capital are not worked out well enough. •Partly as a result of this, the debate often got bogged down in a discussion about the effectiveness of concrete measures, instruments, or funds. (However, this was also caused by giving stakeholders a strong voice.) •The method of choosing requirements, indicators, and sometimes also stocks was too subjective and therefore was too sensitive to change. Moreover, the way the norms were selected was not always transparent. •Although participants in the end tended to appreciate the method, they had some problems getting acquainted with it at first. The degree of abstraction is considered high. Disciplines and topics are linked in new ways. Differences in Place and TimeAs explained earlier, the idea of developing a model to assess regional sustainable development was broadly supported in the province of Brabant, more widely so than in the other three provinces. But there are more differences. In 1999, when the project started in Brabant, the economy in the Netherlands—and even more in Brabant—was booming, and it was a time of political optimism. The assessment in the other provinces was done after the ICT bubble burst and the 9/11 attacks took place. The promotion of sustainable development became a lower priority in the Netherlands, and the perception of it changed. Economic growth became a top priority again, along with another and rather new concern: security. These concerns clearly affected the perceptions and wishes of the stakeholders and influenced the selection in all three provinces. This is one of the possible drawbacks of relying heavily on stakeholders. However, physical, economic, and sociocultural disparities were more important in explaining the differences between the provinces. Some of these differences are as follow: •Brabant and Limburg have sandy soils; Zeeland and Flevoland have clay soils. •In Limburg minerals are extracted; this is not the case in Zeeland and Flevoland. •Brabant has a lot of manufacturing industries. These are nearly absent from Flevoland, where agriculture and the service industries are important. •Aging of the population is not an issue in Flevoland but is an important one in the other provinces (e.g., in the countryside in Brabant). The Telos Method Itself as an IndicatorThe Telos method is, first of all, itself an indicator, intended to show what the situation is at a certain moment in a certain political and geographic area with regard to sustainable development. It is a kind of alarm system designed to show what is going well and what needs attention. Indicating trends is considered more important than providing static measurements. However, the better one can measure, the better this purpose will be served. Measuring presupposes the availability of sufficient, reliable, comparable data. Often these requirements have not been fulfilled, as explained earlier. This does not mean that the method cannot be used. Certainly in the initial phase the process is already on track, and thus is a success, if it frames the opinions of people who make decisions, helps to develop a common language, stimulates discussions, and draws attention to the need to develop adequate norms and data and if it provides some concrete indications on the basis of already existing data. The Telos method is still in its infancy. Its main goal is to offer politicians, civil servants, nongovernment organizations, firms, and citizens a tool to discuss sustainable development in general and its state in their own region. The Results ComparedIt is worthwhile to discuss some of the concrete outcomes of the assessments in the different provinces. However, we will limit ourselves to comparing the selection procedures of the stocks, requirements, and indicators in the different provinces. StocksAt first, the idea was to keep very strictly to the set of stocks already formulated by Telos on the basis of desk research. This proved not to be completely possible. Debates with local experts and stakeholders about the structure of capital led to adaptations, especially in the sociocultural capital (Telos 2003). Second, stocks already proved to be defined to some extent by temporal and spatial conditions. This became very clear when we applied the method in the different provinces: •In Limburg, the stocks coincided to a large degree with those formulated for Brabant, although their interpretation differed greatly. The mineral resources stock was added to economic capital. It is very likely that this stock will henceforth be included in every new regional account. But before we can do this, we have to redefine the natural resource stock in ecological capital. •The discussion in Zeeland made it clear that the consumption stock, before inclusion in sociocultural capital, should be deleted. The fact that the experts and stakeholders in Zeeland saw no use for the natural resource stock or for a new stock dealing with mineral resources was interesting. RequirementsWhen the Telos method was applied in other provinces, the hope was to identify a large correspondence in the requirements defined and an overlap of at least 75 percent. The underlying reasoning was that this would allow the development of a generic, usableregional model. The Venn diagram in Figure 19.6 shows the overlap for all provinces. The diagram consists of four rectangles, each representing a province. The area where all provinces overlap is black. Overlap between three (dark gray) or two (light gray) provinces is also represented. The white fields represent indicators without any overlap. The results are remarkable. Only twenty-three requirements overlap everywhere; fourteen are shared by three provinces, fourteen by two provinces, and twenty-eight requirements proved to be completely province-specific. Limburg has defined the most requirements (fifty-two) and also has the most province-specific ones (fourteen). This is partially because of the extra stock added in Limburg. This resulted in four extra requirements. Zeeland used the smallest number of requirements (thirty-nine). But in Zeeland two stocks were left out. If we look at the overlap with Brabant, we see that this overlap is the largest for Flevoland and the smallest for Limburg. As mentioned earlier, Limburg has the largest number of province-specific requirements.

Indicators We also assessed the overlap of indicators, as shown in Figure 19.7. 林堡有最大数量的指标(123), 24 of which are province-specific. Sixty-three indicators are shared by all four provinces, represented in the area where all rectangles overlap. If we look at the overlap of Brabant with the other provinces, we see that Brabant and Limburg share the greatest number of overlaps (83) but also the greatest number of differences (69). But Flevoland and Zeeland have approximately as many overlaps with Brabant (80 and 81 indicators, respectively). OverlapTo calculate the total overlap between the provinces, we formulated the following model. If a requirement or indicator occurs in all four provinces (f4, or a frequency of 4), there is 100 percent overlap; if a requirement occurs in three provinces, the overlap is 75 percent, and so on.

Overlap = f4 x 100% + f3 x 75% + f2 x 50% + f1 x 25% Application of this formula led to the following results3: Requirements: 60% overlap Indicators: 64% overlap |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Continue reading here:Rusong Wang and Juergen Paulussen

Was this article helpful?